Some say the ship’s crow’s nest was invented by Arctic explorer William Scoresby, of Whitby. Others hold that Viking sailors kept a crow in a cage strapped to the top of the main mast, to be released if they got lost; the idea was that the bird had a sixth sense about the direction of the nearest land, so they’d release it and follow the direction it took.

Personally, I’ve never been in a crow’s nest at the top of a mast, as it rolls around in rough seas. But I can imagine how it would feel. Allow me to explain.

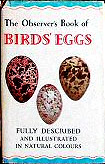

Before I knew much better, at the age of about eight or nine, I’d often go egg collecting.  Finding the nests of sparrows, blackbirds and robins was a bit too easy; blue tits, thrushes, wrens and pigeons were not that much harder. Occasionally you’d come across a wonderful sight, like a flycatcher’s nest, hidden from the path, on the far side of a tree stump, above a little stream. But the challenge was to collect an egg from one of the cleverer birds. Something more rare or difficult to obtain. Like the egg of a carrion crow …

Finding the nests of sparrows, blackbirds and robins was a bit too easy; blue tits, thrushes, wrens and pigeons were not that much harder. Occasionally you’d come across a wonderful sight, like a flycatcher’s nest, hidden from the path, on the far side of a tree stump, above a little stream. But the challenge was to collect an egg from one of the cleverer birds. Something more rare or difficult to obtain. Like the egg of a carrion crow …

Having crossed the brook at the back of our house in Caerphilly, my three chums and I would take the rough, stony path which meandered through fields and hedgerows until we came to a small, damp and rather spooky stone archway under a single track railway. (Of an evening I’d often look out of my bedroom window to watch an incredibly long freight train chugging along this line, its wagons brimming with Welsh coal, hauled by a lonely steam loco. Now and again I’d see a wagon which was just like one of those I had in my Hornby-Dublo train set).

On the other side of the archway the terrain was much steeper and covered with ferns, a great green blanket, dusty with spores – somewhere I always think of when listening to, or reading, Dylan Thomas‘s magnificent poem, Fern Hill. On and on we trekked, as a couple of hours passed by unnoticed.  By the time we reached Rudry – with our parents once more contemplating alerting the police for four missing boys – shadows were lengthening and the wind was getting up. But there, in the distance, we’d see our goal – a line of tall trees complete with its murder of crows, three or four occupied nests of the big black birds perched perilously at the very top of each one.

By the time we reached Rudry – with our parents once more contemplating alerting the police for four missing boys – shadows were lengthening and the wind was getting up. But there, in the distance, we’d see our goal – a line of tall trees complete with its murder of crows, three or four occupied nests of the big black birds perched perilously at the very top of each one.

Soon we were clambering up the thicker lower limbs of our various chosen trees, breaking a route through the foliage, shouting encouragement to one another, onward and upward, till we came to the thinner, more spindly branches, where the birds had built their nests, perhaps eighty feet from ground level. The gathering wind made the treetops sway quite violently; but at that innocent age this was all part of the fun, and indeed I even recall leaning one way and then another to increase the amount of swing. All the while, the big, black crows, who’d evolved with the intelligence to choose these high rise places of supposed safety for their homes, circled threateningly above our heads.

Finally, the moment of triumph. Stretching my arm – and my luck – as far as it would reach, I could put my hand into a nest and feel the warmth of the clutch of four or five eggs in its twiggy home. I just wanted one, one specimen to bring back and add to my collection (my “museum”), which included single examples of the eggs of many other birds.

The most notable thing about the carrion crow’s egg was its size – considerably bigger than that of nearly all the others I collected (see illustration from Wikipedia below). Back home, after a good hiding and being sent to my room, using one of my mother’s sewing needles I’d make a tiny hole in each end and ‘blow’ the egg to remove its contents. Then I’d position it, suitably labelled, in a cotton wool-lined shoebox, alongside the other specimens. It was a thing of great beauty and wonder, though I’m afraid I was the only visitor to my museum. Of course I have pangs of conscience now, about having stolen eggs in this way; but in the case of crows I also note that they, like some other birds in the corvid family, steal eggs from other birds’ nests.

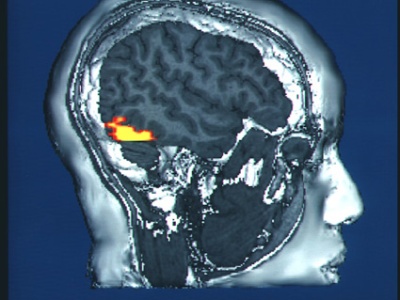

Lest there be any doubt that crows are indeed very clever, a fascinating piece of academic research, published recently, proves it. In a carefully controlled experiment, crows were tested on their ability to relate visual stimuli of varying sizes, shapes and colours to rewards. The most startling finding was the crows’ ability to think in an analogical way – seeing relationships between the format of the stimuli and the reward for the actions they took. In other words, crows are capable of abstract thought.

Here are the researchers’ conclusions:

“Our results thus constitute unprecedented behavioral evidence of analogical reasoning by a nonprimate animal. They therefore add to growing research undermining the influential claims of such famous philosophers as René Descartes and John Locke that only humans are capable of abstract thought. Relational reasoning — particularly appreciating the relation between relations, as in analogies — can no longer be deemed to be the unique pinnacle of human cognition.

“It may be no accident that crows performed so impressively in our study; they stand out among birds in their highly developed neuroanatomy. More generally, mounting evidence indicates that although birds do not have a brain structure that is homologous to the mammalian prefrontal cortex, the avian nidopallium caudolaterale may effectively mediate complex cognitive functions, perhaps representing a case of convergent evolution”.

Yes, there’s something about crows. They’re not hawks; we tend not to think of them as dangerous hook-billed predators that just might attack us and tear at our flesh as an eagle or vulture might.  But maybe one day they could turn on us? In their general demeanour, they always seem to be thinking things through. Their head goes to one side, as they weigh up a particular situation. What are they thinking? What are they plotting?

But maybe one day they could turn on us? In their general demeanour, they always seem to be thinking things through. Their head goes to one side, as they weigh up a particular situation. What are they thinking? What are they plotting?

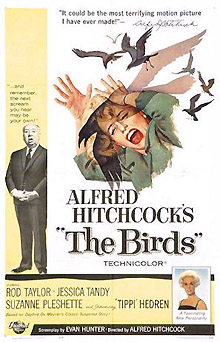

Alfred Hitchcock played on this irrational uncertainty in his classic horror movie The Birds.

The arrival of a newcomer (played by Tippi Hedren) in the town of Bodega Bay passes largely unnoticed by its human residents. But soon, for no apparent reason, the local bird population begins a series of increasingly vicious attacks. No-one can understand why. Yes, there are gulls and other birds involved … but it’s crows that stand out as the main attack force, as the mysterious and co-ordinated assaults on the innocent human population become ever more violent. They gather in trees, on the roofs of buildings and in great flocks overhead, like alien invaders intent on taking over the world.

The question is why? And, of course, there is no answer. No-one knows what’s going on in their minds. Hitchcock’s climactic ending sees the crows watching in restless, black, fluttering armies, their human targets moving gingerly towards the vehicle in which they hope to make their escape …

In a completely different setting, I once experienced the damaging effect of a crow’s incursion into everyday life in, of all places, an advertising presentation, back in the mid-‘seventies.

Thomas Cook had had a bad trading year, both in its Retail and its Holidays business. The six-strong McCanns team, of which I was part, knew we had to be on our mettle to hang onto the business. This presentation had taken some months to put together. Success was vital. On the other side of the boardroom table, the client’s marketing director, flanked by his deputy and other members of his department, made it clear that he needed to be impressed. Early Spring sunshine flooded into the room through a large, sealed, plate glass window at one end. Outside was a small, enclosed quadrangle, which seemed to have no entrance or other window, as though the architect had been unable to find a use for that section of the site.

Opening remarks out of the way, the researcher launched into some key findings. It had all seemed rather fascinating in rehearsal; but in the bright morning light, maybe it wasn’t quite so riveting. Out in the sunshine, a large crow, undercarriage down, glided silently onto the gravel floor of the quadrangle. It marched forward to greet the other crow that it could see reflected in the mirror-like surface of the window.

The researcher was just beginning to struggle for attention. People’s eyes began to wander to the window, to the antics of the crow, who was clearly admiring the sheer beauty of the other bird. As it marched up and down, its actions were matched by identical movements of its new-found friend. They were getting on fine.

At long last, the researcher summed up the key findings, to the synchronised swivelling of eyeballs away from the crow and back to the noisy clunking of the carousel of slides. Now it was my turn.

This was the point at which the crow decided to use a tried-and-tested gambit. It tapped on the beak of the other crow, clearly signalling a desire to take the relationship to another level. Not to be outdone, I decided, on reflection, to go with my own pun-laden introduction, in an attempt to wrest the client’s attention back from the ever more excited suitor outside. The tapping continued relentlessly. The head of the account team strolled over to the window, and did his best to shoo the bird away. Unfortunately, it had no effect – the sunlit reflection made the glass opaque.

And so the presentation proceeded, our team making desperate attempts to counter the tap-tap-tapping and increasingly hilarious cavorting of the crow. It was not my own finest hour … but thanks to some excellent creative work, we retained the business. I still wonder whether the crow had been trained by a rival agency to disrupt our efforts. I’ll never know for sure.

Crows may not be hawks. But they seem to me to have much more in common with hawks than with “cuddly” birds like robins and thrushes. When I see a crow, I almost see a person; someone who maybe would like to take advantage, someone plotting something, someone who could easily upset the apple cart if they had the mind to. In ornithological terms, a wolf in sheep’s clothing, perhaps.

Although its subject is obviously not crows, one of my favourite poems, Hawk Roosting, by Ted Hughes, expresses some of what I think about the brooding menace of crows.

Hawk Roosting

I sit in the top of the wood, my eyes closed.

Inaction, no falsifying dream

Between my hooked head and hooked feet:

Or in sleep rehearse perfect kills and eat.

The convenience of the high trees!

The air’s buoyancy and the sun’s ray

Are of advantage to me;

And the earth’s face upward for my inspection.

My feet are locked upon the rough bark.

It took the whole of Creation

To produce my foot, my each feather:

Now I hold Creation in my foot

Or fly up, and revolve it all slowly –

I kill where I please because it is all mine.

There is no sophistry in my body:

My manners are tearing off heads –

The allotment of death.

For the one path of my flight is direct

Through the bones of the living.

No arguments assert my right:

The sun is behind me.

Nothing has changed since I began.

My eye has permitted no change.

I am going to keep things like this.

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

Note: another very interesting research study on crows – Corvid Cognition, by Nicola Clayton and Nathan Emery – together with links to further reading, can be found on the Science Direct website here).

Image credits:

Corvus corone cornix eggs – by Klaus Rassinger und Gerhard Cammerer, Museum Wiesbaden (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons

The Birds poster – copyrighted by Universal Pictures Co., Inc.. (http://www.impawards.com/1963/birds.html IMP) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Corvus corone (carrion crow) photograph – by Adam Kumiszcza (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)%5D, via Wikimedia Commons